Is openness in AI development a good thing?

It's complicated and depends on your faith in institutions

Introduction

Although recent hype is starting to cool, AI is still developing at a tremendous pace. In my last post, I talked about the transformer architecture. This architecture, which uses the attention mechanism, has been applied to achieve state of the art results in many different areas of machine learning. Many are finding success on a variety of problems by applying the transformer architecture to build “foundation models”. These are very large (10s of billions of parameters) transformer models trained on large amount of data. This training requires gigantic, expensive supercomputers. They gain a general ability in a given area (such as language, vision, audio processing etc). Through a process called fine-tuning, these generally capable models can then learn more specific business tasks downstream. For example, Meta recently released LLAMA-2, which is a language foundation model with general capabilities in language processing. With a few thousand high quality examples, this “base” model can be fine-tuned in a specific domain (such as legal analysis) which greatly improves its performance at that specific task at the cost of reducing its generality. This is an inherent trade off.

Because of the cost of pretraining a foundation model is prohibitive, only big tech companies can produce them. These models are usually locked behind some sort of pay per use API or chat interface (as in the case of GPT models) and heavily fine-tuned to make output more “useful” through reinforcement learning with human feedback (RLHF). Some compare the RLHF process to a lobotomy as we don’t know what it does to the capabilities of the underlying model. Although many people argue RLHF is necessary to make generative AI useful, recent research by Meta AI suggests that just about all of the capabilities are embedded in the pre-trained model and that only a few well crafted examples are required to fine-tune the model towards outputting in a useful format. There are also concerns that models are fine-tuned to reflect the worldview of their creators: rich, young, male, liberal or libertarian, atheistic, white/asian/indian San Fransisco based AI engineers. These people are definitely not representative of the general population of the world.

One of the most obvious lessons of 20th century history is that technological progress confers wealth to its corporate creators and military power to their countries. Joe Biden and Rishi Sunak recently met with industry leaders such as DeepMind, OpenAI, and Meta. China banned LLMs because they can’t RLHF them enough to stop mentioning Tienanmen Square. Because of what is at stake, there is fierce debate on how this technology should be developed and deployed, however broadly speaking, there are two main approaches; closed and open.

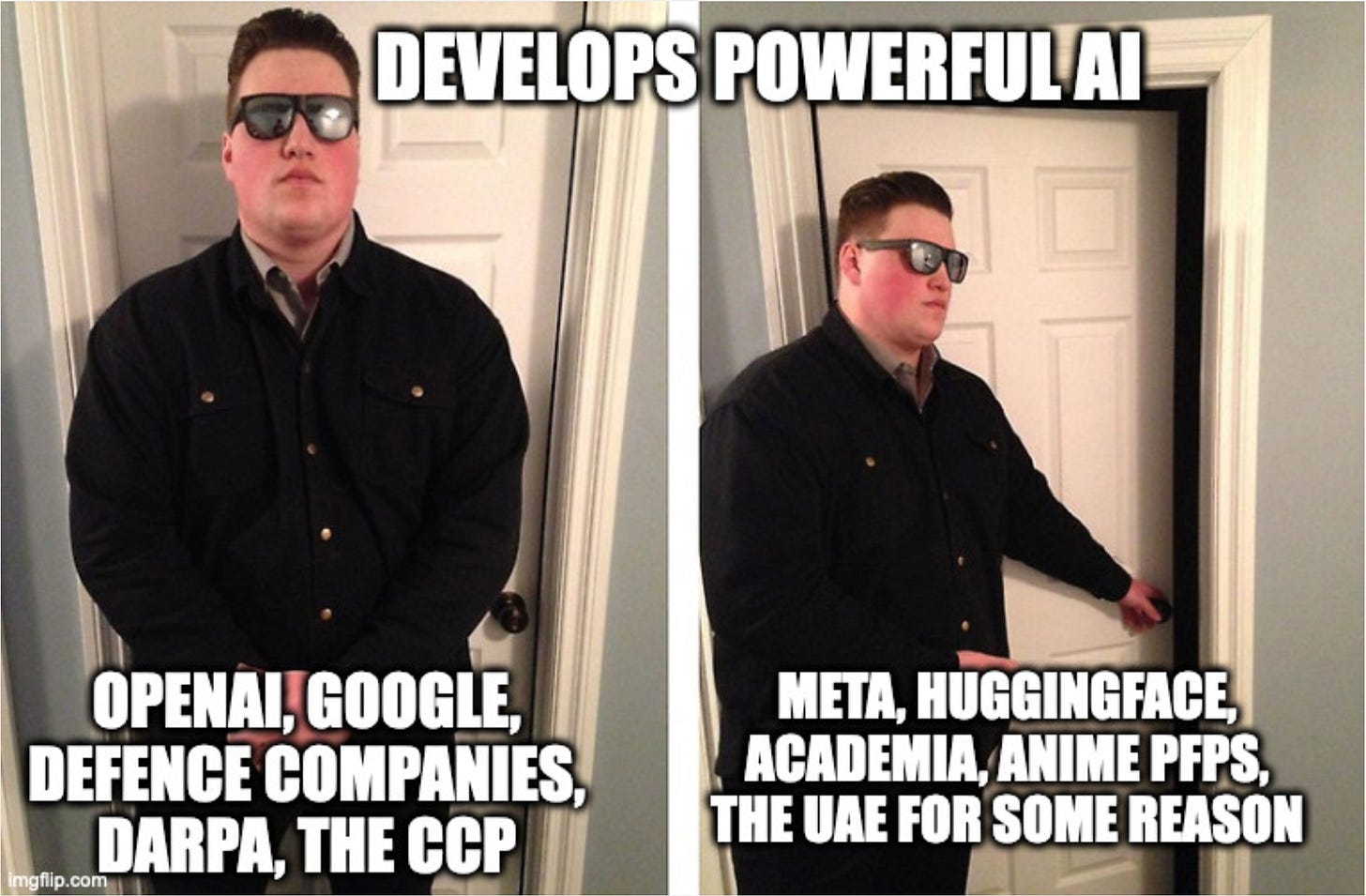

The current players and some recent advancements

Ironically, the biggest player on the closed side is “Open” AI, who is developing the GPT-4, chatGPT, etc. Open AI used to be a non-profit that was dedicated towards releasing all of its models open source to make sure that AI developed democratically. However since then they have taken a lot of funding from Microsoft and decided that their models are too powerful to release to the general public, although they are allowing Microsoft to use them in their unhinged Bing search model.

On the open science side, Meta (formerly Facebook) AI is the big player here. Meta AI has consistently released high-quality open source foundation models to researchers and the general public. Recently they produced SegmentAnything, an underrated and powerful computer vision foundation model, and the far more famous LLAMA which is a 65 billion parameter open source large language model similar to GPT3. Although they published a paper detailing LLAMA architecture (unlike OpenAI’s paper on GPT4 which was very light on info) they only allowed researchers to access its weights at first. Then one of the researchers promptly leaked it to 4chan. If you have the weights, you can now run it on a 2020 or newer MacBook locally using software called LLaMa/CPP (a rewrite of the inference engine in the faster language C++ instead of Python). In terms of quality its fine-tuned version (InstructLLama) it is slightly worse than the free version of chatGPT although through algorithmic advances such as QLORA have made it so that open source models are getting a better and cheaper to train. (Update: when I had already written this article, Meta released a new version of LLAMA, LLAMA2, which has an open source commercial license and is on par with Chat-GPT in terms of power.)

There is also Google, which doesn’t neatly fit into either bucket. They were the original creators of the paper that introduced the transformer model that powered this recent wave of AI, but they have also massively held back a lot of their capabilities, out of general concern for safety, but possibly also out of concern of undermining their own business model.

Some within Google are pessimistic about their ability to adapt. In the now infamous essay which was circulated throughout Google titled “We have no moat”, a software engineer bemoaned the rapid development of open source AI represented by the LLaMa series, LLaMa/CPP, QLORA, etc. Google is one of the most profitable companies in human history, but its dominance relies on people using its search engine to answer questions. For a lot of questions however, up to date information is not required, and it is possible (although I am skeptical) that in the future Large Language Models tendency to make shit up will be fixed, either through the models developing symbolic understanding, or through engineering methods, i.e integrating language models with extrernal databases so they “ground” their answer in facts. A good example is the recent model ChatLAW, which is able to produce legal advice with far less hallucination that its open source base model (LLAMA-1). To simplify how it works, the user’s query is passed into a language model, which extracts keywords. The keywords are then used to query a database, and the answers and references are passed to another LLM, which formulates an answer that summarises and cites the reference material. The user can then verify the citations, which creates trust.

So there are two possible avenues for solving the hallucination problem. I truthfully have no idea if either will succeed, but if they do, some people may stop searching for stuff online, as they can just ask their chatbots that they can run locally on their laptop. This could be a massive boon for end user privacy and productivity but could destroy Google’s business model. My personal view is that if it is possible to make it, a “Linux” of chat-GPT (i.e an open source, private.and hallucination free) chat-GPT clone would wrest a lot of control back from the hands of big tech and give it back to the average consumer.

Many tech commentators have said Google no longer has the institutional agility to effectively counterpunch. However, don’t rule out their recently absorbed subsidiary DeepMind, who has less of Google’s sclerotic bureaucracy and is still publishing high level research. In fact, they are currently preparing to counterattack with a Chat-GPT like model which also integrates some of the planning capabilities that made their AlphaZero/AlphaGo model so powerful. Time will tell if the new Google Brain / DeepMind partnership will retain the dynamism of DeepMind and what approach they will take. At this point I can see them going either open or closed depending on what Google wants.

Some arguments for and against openness

Releasers vs Controllers

In a recent interview with Lex Fridman, notorious hacker George Hotz outlined a certain view on openness in AI development, which I feel is a good summary of the popular case for openness you may see amongst what I call the “Hacker News” crowd. I will call those who are for open source development the releasers, and those who think we should develop in a closed and regulated manner the controllers.

In the releaser’s view, it unlikely that we stop AI development now. This is because we are in an arms race. He doesn’t go into too much detail on this, but I can expand. I think it is useful to think of this arms race as happening at two incentive scales; global and national. Of course, their are interactions between these scales, but it is a useful heuristic because it highlights the different incentives.

Firstly, within countries (America mostly), there is a commercial AI arms race.

Most powerful western AI companies (OpenAI, Google, etc) are in America which has a light touch for regulation as well as high regulatory capture and political corruption. We shouldn’t expect regulation to stop development as this would lead to curtailment of corporate profits

Because of the large financial incentives for developing powerful AI, an arms race condition has been triggered though venture capitalist hype, leading to investment. This investment will only be stopped by a massive reduction in hype due to product failures (think crypto’s arc from 2021-2022). However unlike crypto, there is a lot of empirical evidence that AI will meet at least some of its promise in delivering monetizable value and as such investment is unlikely to dry up and stop the arms race condition.

Zooming out from the financially driven, national arms race, there is a literal global arms race at the international scale driven by geopolitical conditions. This is the application of AI to warfare to gain military superiority. Some current, already existing examples are offensive and defensive autonomous drones, AI fighter pilots, missile defence systems, and automated influence operations.

Although there are entities such as the United Nations for controlling arms, they have had mixed success in the past, as viewers of the recent movie “Oppenheimer” can attest to. Personally amid the Ukraine war and recent tensions between the two global AI superpowers China & USA, I think this internation arms race condition will continue.

Therefore, we can assume more and more powerful AI development will continue. George also disagrees that we should worry about trying to control super intelligent AI or existential risk, which I agree with.

This isn’t because he believes these risks don’t exist, but because we can’t predict what the architectures of super intelligent AI will look like, assuming it is even possible. Therefore it doesn’t make sense to try to figure out how to control it now. It is akin to trying to figure out how to solve a math problem in the future, when you dont know what the problem will be asking, or if it will be algerba, calculus or number theory, etc. You can develop approaches that are generally helpful for controlling all possible upcoming AIs, but this may in turn cause an acceleration of AI development. A good example of this is recent research on understanding why AI models do what they do (in AI research jargon, this is called interpretability). The argument is that a greater understanding of neural network will give us a greater chance of controlling them in the future. However I think it’s just as likely a greater understanding of these models will lead to an increase in the speed of their development.

What releasers think you should be afraid of

George’s main concern is the massive power that capable AI will confer. As we have seen, technology confers power to those who can use it effectively. If AI development is highly controlled and stays behind an API like in the OpenAI case, that confers massive power to large companies like OpenAI and the governments which control them. How you feel about this depends on your view of these private and public institutions. For me personally, this seems like an undesirable outcome, as I have a low trust in governments and corporations.

So the main risk comes not from the typical example of terminator AI (or the nerd version, paperclip maximising AI). The real danger comes from the use of AI by bad humans, or even worse: humans with good intentions who feel a need to control others. In this scenario, open source AI allows people to use AI to defend themself from these bad AI and power is diffused instead of concentrated. For example, to defend against AI powered misinformation operations, you could have an AI browser plugin than can reliably identify and automatically filter propaganda while reading the internet.

The controller view

There are several strong arguments against the open development of AI. I think the best one hinges on the fact that it will lead to more powerful, ubiquitous AI faster, and that because of this, human power will be augmented in uncontrollable and unpredictable ways.

Open sourcing all models will massively speed up the development of AI. If you don’t think that us having super powerful AI soon is good, then this is a concern. For example, we don’t really have any good regulatory framework or social adaption in place to allow us to ameliorate whatever bad outcomes come with AI, and if we open source it and development is accelerated, we will have even less time to put things in place to allow us to adapt.

As a result of quickly improving AI, humans will have more intelligence. Because of economic and national security incentives, this will lead to more development of science and technology, which will further increase human capability, without also increasing out corresponding political, social, moral and spiritual wisdom. For example, what if AI allows anyone the capability to engineer a super virus 100x as bad as COVID? The invention of this technology need not coincide with an increase in our empathy and kindness.

Especially if AI is open source and cannot be monitored, criminals can use it to commit crimes more effectively, or repressive governments to commit acts of violence, etc. There may be an inherent asymmetry where an increase in AI capability makes it way easier for people to fuck things up, without making it way easier to defend people or heal them.

Thesis; Antithesis; Synthesis

As an AI engineer (albeit one working on applied projects, not capabilities), I think about the morality of open AI development a lot. This essay has been a snapshot in my thinking, based on an intuition I have developed through studying, working, and talking to other AI people. In the end, I think a balanced approach is needed. I came up with a simple maxim that sums up the situation we are in.

”Problems require co-ordination at the level at which they occur”

AI is a problem that will affect everyone. For it to develop in a way that benefits everyone maximally, I think we need global co-ordination to develop common sense, minimalist legislation. This would be an agreement between governments to not develop and deploy AI for military purposes, similar to the international ban on chemical and biological weapons.

Secondly, at the level of regulation of domestic AI, this is a poitical problem that is much more up to individual countries. Governments should decide the comfort levels that they have with the deployment of AI and will regulate AI deployment and access within their own borders, “great-firewall” style.

As to the titular question: is open source AI development good? I think it depends, mostly on the unfolding regulatory enviroment. If there is good regulation in the future that prevents misuse, open source AI development can continue apace, and people accross the world will safely apply it to positive applications such as medicine to benefit humanity. However if governments continue to rule out AI arms controls (as US, Russia, China etc have so far) and fail to regulate harmful commercial applications of AI such as engagement hacking I think it becomes unethical to develop open source AI capabilities, as you are contributing to the problem. I don’t buy the argument that open source AI will protect you from bad actors. It is a libertarian fantasy that you can just can outsmart bad institutions if you are good enough at tech, the reality is that they have so much more funding and momentum that the average person will never be able to protect themselves.